France is one of those places that I never imagined myself traversing. When I think about France, I must shamefully admit that I can only conjure up the many stereotypes that have made their way into media. So when I was offered the opportunity to visit France over a two week holiday, I wasn’t exactly sure what I wanted to explore. However, I was not without due diligence. I went to the local library to pick up The Discovery of France: Picador Classic by British author Graham Robb. The travelogue documented the writer’s historical examinations into the localities he visited in his bicycle tour throughout the country. When I completed it about a week after, I felt somewhat equipped with the French cultural context. But unlike other occasions, I did not feel confident.

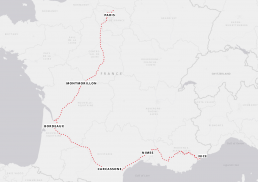

We arrived in Paris by sunrise and prepared ourselves. This was going to be a two-week journey through the South of France. I was only familiar with shades of Paris, having visited the city over a decade ago. This time, we truly were going into uncharted territory into the French heartlands. This time around, I left the shaping of the itinerary to our friends. I knew the main beats of the journey, but I did not know France enough to claim what localities or culture was the must-see. When we left the airport and headed South, we charted the first sight of our journey: The Palace of Versailles.

Palace of Versailles

French history is incomplete without a mention of Versailles, the opulent palace, and the royal family that inhabited it. As we spent hours going through the many rooms and halls, it became painfully clear to me how this excessive display of wealth would have drawn the ire of the French proletariat, specifically Parisians. The different King Louis’ throughout the generations had built the palace to reflect their status as rulers. You can see this in the intricate designs on the walls, pillars, doorways, and so forth. No detail was spared, and the extensive use of expensive materials such as gold was certainly a testament to that. So fascinating was this period of French history that a period drama, Versailles, was produced, dramatising the events that took place in the palace.

However, the many iterations of the French Revolution saw the palace vacated by the royals and taken over subsequently by the self-appointed Emperor Napolean, the Germans and finally – returning to the public. While the palace has seen global importance during the signing of the Treaty of Versailles at the end of World War 1, it is now a heritage site that sees thousands of visitors daily. I was impressed at its expansiveness, but certainly not by its excessiveness.

Montmorillon

We spent the entire day at the Palace of Versailles and departed for Montmorillon by dusk. Our lodgings in this town was a manor house owned by a friend and colleague, which was kindly offered for my holiday with friends. I was unfamiliar with French manor homes, and this would be a first-time experience. Owning a manor, or as it is known in French, châteaux (pronounced shah-toh) is no small thing. Taking ownership of a slice of French cultural and historical architecture is a responsibility of itself and can be a costly investment. However, there is a market for bargain châteaux. Many of these cost under €600,000 and are located in rural France. It can be assumed that these manors were formerly resided by an aristocratic family surrounded by a peasant community.

Montmorillon was one such town. Known as The City of Writing and Bookmaking, Montmorillon has many established generational businesses dedicated to bookmaking, such as calligraphy, book-binding, and rare collections. Book towns like these concentrate their local economy on the book trade. They typically belong to the International Organisation of Book Towns. It is an impressive effort in preserving the tradition of physical bookmaking, particularly in an age where digitalisation has become a prefered mode of consuming the written word. It is also an effort in modelling sustainable rural tourism, where historical economies and identity is preserved and integrated into the local economy.

I did not realise it then, but I had actually visited a book town once. And that was then I was in Tokyo, going through the Jinbōchō district. Montmorillon’s book town was of a different feel. One with a European touch more dedicated to the craft of physical bookmaking than it was in the production of knowledge and literature. But it was enticing nonetheless to a book lover like myself.

My friends and I spent a few days in Montmorillon, also taking the opportunity to explore other surrounding towns such as Limoges and Oradour-sur-Glane. The latter is a town with a tragic history. Over 600 of its inhabitants were massacred, and the town razed to the ground by the German Nazis in the 1940s. The ruins were maintained as a memorial and museum, a reminder. A quiet and haunting spell envelops the entire village as you walk through the ruins of what seemed to be old shop lots and houses. The visitors spoke in hushed voices, if at all.

There was a grimness to the sad history of this place. Though I did not have a shared history of the Holocaust and the ravages of World War 2, the language of pain and memory is universal. To this day, I still think about those ruins: the charred vehicles, the rusted toys and the rows of memorial graves.

Bourg

Bourg is a quiet, small port-town that sits at the Gironde estuary. It is surrounded by vineyards and has an arresting panoramic view of its surroundings. The town’s history is decorated by multiple invasions, but also, due to its strategic location, protected the region for centuries. The port-town is now known more for its surrounding wineries. Many wine aficionados pass through to get to generational established vineyards in the area.

Towns like Bourg remind me of the multitude of localities across Europe that once had a notable past in its region. Were it a town, village, or city – the globalisation of national economies drew labour away from the far reaches into the country and focused them into an urban centre, either nearby or hundreds of miles away. In Bourg’s case, Bordeaux city was its urban centre. While French regional development policy is strictly decentralised and offered maximum autonomy, developments throughout the country were inconsistent or uniquely different depending on local government resources. In this regard, Bourg’s economy relies on the over 400 winemaker businesses that form as principal suppliers for the renowned Bordeaux wine brand. As the world changes, so do towns like Bourg to survive.

Bordeaux

Bourg to its closest urban centre, Bordeaux, is about an hour’s drive away. The city owes its fame to its wine economy, and its urban development certainly reflects that. The historic city is walkable, and one could easily get lost in its many turns and corners. Unfortunately, we did not spend much longer than a few hours into the afternoon in the city. However, I was able to at least soak up a sense of architectural marvel and, at one point, found myself in an antiquarian bookstore admiring an entire set of the Harry Potter series in full French.

The danger of big cities like Bordeaux is that it also grows into pockets of tourist traps. Many cultural attractions we passed or entered were flocked by foreign tour groups, backpackers or travellers like ourselves. In the periphery, waiting, are touts. Though my experience dealing with touts in France was not as severe as when I went through Italy – it is an established fact that in any major city with a tourism draw, one cannot escape individuals and syndicates looking to make a quick buck.

Speaking of tourist traps, one of the most challenging, if not frustrating, aspects of travelling is the search for the “authentic”. While this has been discussed at length for experiences and community, the same could also be extended for food and cuisine. One such dish that we fell into the tourist trap to was the bouillabaisse. It is a stew that is a composite of different types of vegetables and served with rockfish. While the dish originates from Marseille in the far south of France, we were far from its origins – and decided to give it a go at one of the many restaurants on the kerbside of the city.

The bouillabaisse prepared by this restaurant was interesting. It was a generous seving of mixed seafood in a tomato-based broth. The seafood, to the restaurant’s credit tasted fresh. Still, it certainly did not feel like it had a touch of what one can argue was authentic. And how could it? We were in Bordeaux, not Marsaille. It isn’t unusual for big cities to have other regional dishes and offer a corrupted sample. One, however, needs to be prepared to accept that their expectations need to be lowered. If you wanted to the real thing: go there. And even if you did, there is no guarantee you will find that it is authentic.

Carcassonne

Suppose you have never been to a castle fortress. In that case, Carcassonne gives an accurate idea of how a medieval fortress would look like. Cité de Carcassonne, the city fortress, is perched on a hill and commands a strategic view of its surroundings. Out of all the places we’ve been to so far, this was the one I found most interesting. We came to the fortress early in the morning and entered the walls before the shops were open. My wife and I were in no particular mood to follow historical tours that morning, so we diverged from our friends and decided to explore the fortress grounds.

Cité de Carcassonne is quiet in the early mornings, and you get to fully appreciate its architectural and engineering details. This fortress, after all, was a sustainable township of its own. The fortress could accommodate thousands, and you can certainly see how it had a life of its own. The streets, though narrow, could accommodate for stores that sold wares and goods. A tight-knit urban community living within proximity to the seat of power. The cobblestone paths told a history of those who resided within these walls and towers. Despite restoration efforts in the late 1800s, one could certainly still appreciate the depth of history and memory the Cité had.

There were moments where we would turn a corner where there were no modern restaurants or stores and imagine a medieval soldier patrolling down the footpath. Or a thief running through the knock turn alleyways, trying to escape his pursuers. These are scenes out of a medieval TV show or movie, but the setting certainly lends to that imagination.

I must admit it is this part of the journey where my recollection (and maybe memorable impressions) have blurred into one another. I will, from here on, deliver this recollection in the form of photographs. I will add brief notes and impressions where I feel necessary.

Nîmes

Pont du Gard

A history and engineering lesson. I found Pont du Gard fascinating in how it introduced me to the concept of aqueducts. Nîmes, the city we stopped by the day before, was a Roman Empire outpost from around the 4th to 13th century. The Pont du Gard is a Roman aqueduct designed to channel water supply from the Gardon river to the city. There was a museum at its entrance, which offered extensive information on the importance of urban sanitation and its role in maintaining cleanliness and reduce urban diseases and ills. I recall one particular section of the museum that told of how water constantly flowed through the streets of Nîmes – clearing the pathways of human and animal filth. Without the flowing water, the dirtiness of such urban conditions would have led to public health consequences – a reality for many urban environments many centuries ago.

Seen in person, the Pont du Gard is a marvel of architecture. The structure is almost 50 meters in height and varies in its length depending on the levels. The deep-blue river flowed calmly beneath it. Even after it fell into disuse many years after the Roman Empire fell, the structure continued to function as a bridge. We found ourselves having a picnic by the riverside, enjoying servings of crusty baguette, slices of cheese, and apples. All while the Pont du Gard stood grandly in front of us.

Avignon

At this point, I must discuss the use of French during our travel. Typically before I go anywhere, I would make it a point to pick up keywords and phrases. The bare minimum should be: hello, please, thank you. Everything else is supplemented by a quick Google Translate with keywords cobbled together in stilted but passable syntax.

We got by using English during our journey throughout France but with initial efforts to communicate in French. Being in France, too, however, means we take stops at cafes to pass the time between. This would be when our other friends are busy sightseeing elsewhere, or my wife and I wanted a breather from the day’s activities.

“Un café au lait, s’il vous plaît” is my most-often used phrase. One coffee with milk, please. A latte, essentially. I could patron a French cafe and hold a simple one-way conversation in French, with the occasional oui thrown in. Back then, one would rely on guidebooks, flipping one before a cashier trying to understand the transaction. Nowadays, it’s as simple as an app with dedicated translations or an internet connection to look it up on Google Translate.

Many have recommended me Duolingo, but I’ve yet to find time to learn languages in such depth.

Aix-en-Provence

Moustiers-Sainte-Marie

I love the hills and mountains. So when this part of the journey offered winding passes through the Alpes de Haute Provence (Alps of Upper Provence) over the upcoming days, I was ecstatic. We were to spend a night in Moustiers-Sainte-Marie, a village on the hill, and it would be prudent to arrive by evening. Driving in the dark between the mountains were not ideal.

Along the almost two-hour drive up, we passed through the lavender fields near the Durance Valley. We were a few months too early and did not chance upon any. I wondered how many thousands had stopped by the side of the road, walked between the shrubs, took photos and then left without so much as an acknowledgement that one had entered another’s land. Moreover so, a land where their livelihoods came from, and they receive nothing much from a random photograph in the middle of their field. This has been a subject of anger for the French farmers when social media incentivised popular photography.

By the time we arrived Moustiers-Sainte-Marie, it was already late evening, and there was a light drizzle. We quickly checked in, took a breather and then scoured the village for dinner.

At this point, I realised I haven’t discussed much French cuisine and food. Apart from the bouillabaisse mentioned earlier (sampled in Bordeaux), much of our fare across France had been interesting, but it had not caught my imagination. I must record that this has less to do with French cuisine and more to do perhaps with my lack of understanding of what the French palate had to offer.

We were on the road half the time, so we would stock up with bread – typically a baguette with some select cheeses and an assortment of fruits. Breakfasts would be pastries ranging from croissants (bought at the town’s local bakery) or pain au chocolat. Lunch would depend mainly on the city or town we were at and how adventurous our palates were that given evening. However, on occasion, my wife and I would treat ourselves to a confectionary. In Bourg, we spent a good time in a pastry store picking out a colour box of macaron flavours. On other occasions, we would sample Éclairs, crepes, madeleines in the different towns we toured by.

When it came to dishes, the most adventurous was a dish of escargots — a distinctively French dish consisting of snails, often the subject of pop culture disgust. However, back home, I’ve consumed my fair share of snails in the form of Siput Sedut Masak Lemak Cili Api. This was no big deal. Mostly though, I ate boring meals that one would find in most continental restaurants – if those meals were not me consuming French bread and cheese in a city park.

This is where I must confess that the one thing the French did impress upon me was the range of cheese available at every turn. I grew accustomed and fond particularly of soft cheese like Brie and Camembert. Although I did not shy away from experimenting with varied options such as Goat’s cheese, we had a board in Moustiers-Sainte-Marie. It was close to dusk; the streets of the mountain town were sleek with drizzling rain. I had just entered La Part des Anges de restaurant, wet like a dog from spending almost twenty minutes trying to capture the sunset across the hills. My wife had then already ordered for me a cheese board, and there it was: three different types of cheeses with accompanying sauces, nuts, and vegetations to eat and elevate the flavours with.

I could not get out of my head that one notable scene in Pixar’s 2007 Ratatouille, where the main character, Remy, taught his brother how to mix different flavours of food, further enhancing one’s culinary experience. The lesson may have been lost on his rat-brother, but I could certainly relate. Especially when it came to cheese and its variety of pairings.

Gorges du Verdon

Castellane

There is a curious feeling when one drives into Castellane. It is a small town and is one of France’s least populated sub-prefectures. When one enters the town, they are met with an unmistakable hill, with a chapel perched on its edge. The town area itself is small; travellers who stay here usually opt to stay in trailer parks or campsites as we have. During the time we were there, many shops were closed and the town centre quiet. In the evenings, there was some life, but the streets were mainly dark. Lit by the dim lights coming from the glass-pane windows and street lights.

The Chapelle Notre Dame du Roc overlooks the entire town, commanding a breathtaking vista enjoyed by pilgrims and modern-day travellers who make their way up a winding path, 903-meters above the town. The hike takes about an hour for both ways up and down and is a challenging yet manageable climb. Along the way, signpost paintings recounted the crucifixion of Jesus Christ, a story told through the visual medium. Visual storytelling is engaging because it spoke to a period when literacy among the populace was low. Much of it was communicated orally and through visual medium such as stained glass art and paintings.

When we arrived at the peak where the chapel rested, the view was certainly worth the climb. One could appreciate the religious experience of Christian pilgrims who made the hike up through rock and stone. According to historical records, pilgrimages to the Notre Dame du Roc has been taking place since the 14th century.

Despite being only a brief stop in this small town, I felt most rejuvenated here among nature; the gushing rivers and mountains. After a simple dinner, we retreated back to our campsite. I awoke in the middle of the night, somewhere past 2 o’clock in the morning, went outside and gazed in the marvel of the constellations. Stars that backdropped the gorgeous mountain ranges, despite the latter being shrouded in shadow. There is a magnificence to nature, and tonight certainly demonstrated it.

This brief respite is a necessary breather before we made our way to Nice, the final leg of our journey, and a seaside city teeming with urban life.

Nice

The moment we arrived Nice, I felt urban energy that I love and am well-acquainted with. Moreover, the architecture felt strongly Italian due to its proximity and intertwining history with its neighbour, Italy. Nice, however, is mainly known for its appeal to the upper classes of international society. Being one of France’s most visited cities, it has also been popularised in media — most iconic among them being Elton John’s ‘I’m Still Standing’ music video.

As an urban explorer, my impressions of Nice has to be drawn from absorbing its environment and life on the streets. So over an afternoon, I took to exploring the city’s different districts. Both closer to the seafront, mostly tourist-driven. As well as towards the hills, inhabited mainly by locals and the working class.

Walking through the streets of Nice reminded me why I enjoyed the experience of cities — the density, the compactness and all the life in between. Perhaps it also called out to my explorative nature, where I took the opportunity to go from one alleyway into another; a cognitive map of the city unfolding in my mind with every turn. European cities are delightful because there is a preservation of heritage and history in their architecture and layout, compared to newer cities. In a way, there is a melding and imaginary crossing between the new and old.

This continuity is what gives a city identity and a distinctive statement. Without continuity; genealogy wired into its urban planning, architecture or people — how can a city go beyond a space of economic opportunity?

In my two weeks travelling through Southern France, what have I to reflect on? As I mentioned earlier, I have always thought of France as an impression created by the media. Long-dragged cigarettes, coffee, pastries and a nation of cynical philosophy. The latter being an intellectual tradition so strongly defended. But those are the media trappings created by the capital city of Paris.

What would one find if they ventured elsewhere? What I found was a kaleidoscope of cultures, all bearing the same flag. This was what Graham Robb tried to impress upon me in the pages of The Discovery of France. Historically, France is a modern idea united by a modern constitution. But a tour into its different provinces and its people would illuminate unique cloisters of shared history and distinct identities.

I regret not spending more time in each city or town that I passed – many I only spent about a day before moving to the next. But my impressions were positive. And I hope with certainty to return to France – not Paris, and for the nation to allow me to see more of it.