Before the pandemic, drivers in Kuala Lumpur spent over a week in traffic1Tomtom.com (2022). Kuala Lumpur traffic report. Available at: https://www.tomtom.com/en_gb/traffic-index/kuala-lumpur-traffic/. While congestion levels improved over the pandemic years (under 30% since last 2020), traffic is now expected to creep back to higher levels as the country moves into the endemic phase. While the government has been busy with highway development projects, the Kuala Lumpur City Council (DBKL) once again mulls the question of congestion charging2Chan, M. (2022). RMK-12: Highway development to be reviewed – reasonable toll rates for rakyat, fair investor returns. Paul Tan’s Automotive News. Available at: https://paultan.org/2021/09/27/rmk-12-highway-development-to-be-reviewed-reasonable-toll-rates-for-rakyat-fair-investor-returns..

Congestion charging as a way to manage traffic and pollution has been proposed multiple times over the decades, either by DBKL or elected representatives. But its lack of implementation is due to the political sensitivity of applying levies on the public; an unpopular move. But what is congestion charging? What are its objectives and how is it typically implemented?

What is congestion charging?

Congestion charging is a fee paid by private transport users (i.e. cars, motorcycles) when they drive into the city. The main point of congestion charging is to discourage private transport usage in the city centre through financial disincentives. By doing this, the local authority or government aims to shift users from using cars and motorcycles, to adopting more sustainable forms of transportation such as trains or buses. Beyond reducing private transport usage, congestion charging also aims to reduce fuel consumption and pollutant emissions — making the city environment better to live in3Isaksen, E. and Johansen, B. (2021). Congestion pricing, air pollution, and individual-level behavioural responses. Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy Working Paper 390/Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment Working Paper 362. London: London School of Economics and Political Science.

How does congestion charging work?

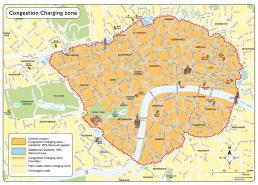

A private vehicle user pays a congestion charge when they enter a designated zone. This is usually the city centre, where activity is expected to be at its highest. For cities like London that implement congestion charging, the levy is usually paid before one enters the zone. In the case where an impromptu journey is made into the zone, the user (whose vehicle plate is registered) will receive a notification for payment post-journey. Payments are typically done online. For London, the congestion charge is paid on a per day basis, with unlimited entries per day.

At its core, congestion charging is also about traffic management. The levy applies for journeys made during specific hours in a day where higher traffic activity is expected. Cameras throughout the zone capture the number plates of vehicles entering the area and determine if a vehicle has been accounted for or not. Other cities use RFID (radio-frequency identification) instead as a means of identification4Ganzera, M. (2020). Traffic Congestion: Addressing One of the Biggest Smart City Challenges with Secure RFID Technology. NXP. Available at: https://www.nxp.com.cn/company/blog/traffic-congestion-addressing-one-of-the-biggest-smart-city-challenges-with-secure-rfid-technology:BL-SMART-CITY-CHALLENGES-SECURE-RFID.

The above map is London’s congestion charging zone, as defined by Transport for London (TfL). The boundary (in dotted red) outlines the area where one is charged for driving their private vehicle in the city. Incidentally, those who stay within the congestion zone receive substantial discounts of up to 90%, should they choose to own a private vehicle5Westminster City Council (2021). Congestion Charge discount for residents within the zone. Available at: https://www.westminster.gov.uk/parking/parking-residents/congestion-charge-discount-residents-within-zone.. Up until recently, London also attempted to incentivise low-emission vehicles by offering a Cleaner Vehicle Discount that entitled owners to get a full discount when entering the congestion zone with a low-emission vehicle6Activa (2019). London toughens Congestion Charge exemptions with new Cleaner Vehicle Discount. Available at: https://www.activacontracts.co.uk/news/london-toughens-congestion-charge-exemptions-with-new-cleaner-vehicle-discount.html. The policy has since been updated to only apply for zero-emission capable vehicles and fully-electric vehicles.

Additionally, certain vehicles are exempt from congestion charges such as registered ride-sharing vehicles, vehicles registered with disabled individuals, and public institution vehicles such as ambulances and fire engines.

Impacts of congestion charging

In both London and Singapore where congestion charging is implemented, traffic was reduced substantially — 20% in the first few months of its introduction in Singapore, and 15% within the first few weeks in London7Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (2021). How Singapore improved traffic with congestion pricing. Available at: https://www.cmap.illinois.gov/updates/all/-/asset_publisher/UIMfSLnFfMB6/content/singapore-congestion-pricing.8Road Traffic Technology (n.d). Central London Congestion Charging, England. Available at: https://www.roadtraffic-technology.com/projects/congestion/.. Beyond the tangible evidence of reduced traffic, congestion charging has long-term impacts. The first is environmental improvements to the urban space. In Stockholm, Sweden, another city with congestion pricing saw carbon emissions decrease by almost 20%, and subsequently, so did asthma-related hospital visits (by 50%)9City & State NY (2019). Going green through congestion pricing. Available at: https://www.cityandstateny.com/policy/2019/04/going-green-through-congestion-pricing/177497/. There are further impacts on public health which will be discussed shortly but in summary of the first point: fewer vehicles mean fewer carbon emissions and noise; making city air cleaner and the environment more bearable to live in.

Secondly, is the improvement of public goods. In cities where congestion charging is implemented, the levy collected is earmarked towards funding public transport, or green initiatives and infrastructure. What this means is that the revenue from congestion charges is used specifically for projects that direct the city towards being more sustainable. From 2003 to 2013, London collected revenue of £2.6 billion from congestion charges, 46% of which was re-invested into improving public transit, public infrastructure and road safety10Evening Standard (2013). Congestion Charge ‘has cost drivers £2.6bn in decade but failed to to cut traffic jams’. Available at: https://www.standard.co.uk/news/transport/congestion-charge-has-cost-drivers-ps2-6bn-in-decade-but-failed-to-cut-traffic-jams-8496627.html. In Milan, revenue from congestion charging was re-invested into public transit, bike-sharing schemes, and pedestrian infrastructure — actions which further deepened public support for congestion charging, as the city’s citizens witnessed positive changes to the urban landscape11Eco-innovation Action Plan – European Commission (2013). Milan: lessons in congestion charging. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/ecoap/about-eco-innovation/good-practices/italy/20130708_milan-lessons-in-congestion-charging_en. The move from private vehicle use to active mobility, i.e. walking, cycling improves public health by making the public engage in active lifestyles.

What needs to be emphasised here is that congestion charging cannot operate in a vacuum. As demonstrated in other cities, revenues from congestion charging are re-invested into public transportation and mobility-related initiatives and infrastructure. This serves to encourage users to adopt more sustainable options of travelling in the city, by making the choice to switch as painless as possible. This will be an important aspect to discuss when it comes to the question of implementing congestion charging in Kuala Lumpur.

Proposing congestion charging in Kuala Lumpur

In DBKL’s Kuala Lumpur Structure Plan 2040, the city council outlined plans for congestion charging, sequestered within the city’s major areas. The 19.2km² zone extends to the edges of the city’s major urban neighbourhoods. The interactive map below is the proposed zone (in red) as well as the roads on which congestion charges would be levied (in orange).

DBKL’s proposed congestion charging zone, referenced from the Kuala Lumpur Structure Plan 2040.

Proposed roads

It is worth noting that in DBKL’s proposal, private vehicle users would only be charged if they drive on select roads within the traffic management zone. The roads are:

- Jalan Parlimen

- Jalan Tuanku Abdul Rahman

- Jalan Raja Abdullah

- Jalan Kia Peng

- Jalan Bukit Bintang

- Jalan Sultan Ismail

- Jalan Pudu

- Jalan Hang Tuah

It is likely that DBKL has considered these 8 roads as having both high volume and traffic, alongside being main arteries that connect to major parts of the city centre. Upon closer inspection, these selected roads capture incoming traffic coming from major expressways from outside Kuala Lumpur. For example, Jalan Sultan Ismail, one of KL’s major roads, captures incoming traffic from North and East Klang Valley. Another example is Jalan Hang Tuah, which is connected to incoming traffic from Cheras via Jalan Loke Yew — another major, high-traffic road.

It would appear that the choice of selected roads is a Phase 1 implementation, in which successive phases may incorporate a zone-wide congestion charge capture — similar to what is practiced in London.

Exemptions and discounts

Census statistics indicate that the Kuala Lumpur region has a population density of 8,157 persons/km², the highest in the country12Department of Statistics Malaysia Official Portal (2022). Launching of report on key findings population and housing census of Malaysia 2020. Available at: https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php. If congestion charging is going to be implemented within a traffic management zone — a zone that has a sizeable working population (73.5%), then considerations must be made to compensate residents who live within this area.

Similarly to London, DBKL could offer up to a 90% discount for a single vehicle. However, this may prove a challenge as Malaysians has one of the highest rates of car ownership globally (93%), with over a half of households stating they own more than one vehicle13Nielsen (2014). Rising Middle Class Will Drive Global Automotive Demand. Available at: https://www.nielsen.com/my/en/press-releases/2014/rising-middle-class-will-drive-global-automotive-demand. To refine the problem even more, motorcycles are a popular mode of private transport among Malaysians, as it is more mobile than a car and allows users to slip through traffic easier14Pew Research Center (2015). Car, bike or motorcycle? Depends on where you live. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/04/16/car-bike-or-motorcycle-depends-on-where-you-live. In Kuala Lumpur, it isn’t unusual to see motorcycles are a chosen form of transport among those who work (and live) in the city. Affordability to own a motorcycle is a major factor in this high adoption rate, especially among the lower-income groups.

If DBKL is to consider a discount for KL residents within the traffic management zone, they will need to clearly define what forms of private transport are covered under the congestion scheme alongside the exemptions. Ideally, to make the objectives and outcomes of congestion charging effective, one household should only be afforded a discount per vehicle, regardless of whether it is a car or motorcycle. This will radically shift travel behaviours, which is why the local authority needs to develop stronger public transport infrastructure and networks to make up for this adjustment.

Improving public transit

The point of congestion pricing is to regulate private vehicle use by charging a levy. In practice, this means discouraging users from driving into the city centre by financially “penalising” them15Tardi, C. (2021). Clearing Up Congestion Pricing. Investopedia. Available at: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/congestion-pricing.asp. The expected behaviour from such a policy is for users to change their travel behaviours by finding alternative means to get into the city. This is where public transportation comes in.

Recently, the Transport Minister indicated that congestion charging would be considered when the MRT3 Circle Line has completed 16Thomas, J. (2022). KL congestion fees possible when MRT3 fully completed. Free Malaysia Today. Available at: https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2022/03/15/kl-congestion-fees-possible-when-mrt3-fully-completed. The logic behind this delay is that the MRT3 project is seen as the metro project to “close the loop” and address coverage gaps in the Greater Klang Valley. The completion of this project means that users will have a stronger reason to switch to public transport (i.e. taking the metro into the city), and those who choose to drive will pay a surcharge for doing so. While this sounds reasonable in theory, in practice, this approach is another delay tactic. Does the MRT3 Circle Line need to be completed before implementing congestion charging?

One of the major challenges for public transport adoption is the lack of first-last mile reliability and connectivity17Azuddin, A. and Omar, N. (2019). Getting Around: Towards a Decent Daily Commute. The Centre. Available at: https://www.centre.my/post/getting-around-towards-decent-daily-commute. While a well-linked metro network is essential to the connectivity of a city (see London and Tokyo), the expansiveness of its feeder bus network and pedestrian access is just as important, if not more. Klang Valley’s public transport landscape currently suffers from weak first-last mile infrastructure, whether in terms of reliability, accessibility, or connectivity. Users may be willing to take the metro into the city, but they will still need to complete their journeys either on foot, by bus or by micro-mobility (i.e. scooters, bicycles). DBKL will need to seriously consider improving its pedestrian infrastructure to make it more safe and accessible if they are serious about encouraging users to walk and take micro-mobility to their destinations within the traffic management zone.

Regarding feeder bus services, the reduction of traffic in the city centre may free up space for buses to move around efficiently. Currently, feeder buses share the same roads with cars and are caught in the same traffic congestion. This negates the time-usefulness of buses, as there is virtually no difference in journey time saved. One would be more inclined to sit in the comfort and privacy of their cars as opposed to sharing a space with other commuters — with the same amount of time spent. There are efforts to resolve this problem. RapidKL recently announced that it would work together with DBKL to enforce dedicated bus lanes in select roads to allow for efficient journeys18Yap, K. (2022) Rapid Bus, DBKL laksana projek percubaan lorong bas. MyRapid. Available at: https://myrapid.com.my/rapid-bus-dbkl-laksana-projek-percubaan-lorong-bas. Although dedicated bus lanes have been available on select roads for over a decade now, their enforcement has been unsatisfactory, if even existent.

Lastly, we return to the claim of the MRT3 Circle Line “closing the loop” and how it may theoretically encourage public transport adoption. In a public presentation last year, MRT Corp said that the park and ride facilities at the station would help reduce the number of private transport users driving into the city. All metro development projects in the Greater Klang Valley take this approach. The interactive map below shows stations across different metro lines with park and ride facilities. As we can see, park and ride facilities are primarily located outside the city centre and traffic management zone (in orange), with the exception of SP10 - Pudu. Park and ride facilities, while strategically sound, do not guarantee that users will switch to taking public transportation into the city. Its usefulness depends on strong first-last mile infrastructures, as we discussed earlier. Users will only fully switch to public transport if the entire journey is more efficient and sensible compared to driving into the city.

Park and ride facilities at stations across the Greater Klang Valley Integrated Rail System.

Revenue and reinvestment

Congestion charging, by and large, is a local authority initiative. This means that its implementation, enforcement and management will be done wholly by DBKL. Typically, in cities that implement congestion charging, the revenue is reinvested into improving public transit systems, micro-mobility infrastructure and transport-related priorities. This is particularly true in London, whereby law, revenues from congestion charging must be reinvested into transport-related initiatives19Centre For Public Impact (CPI) (2016). London’s congestion charge. Available at: https://www.centreforpublicimpact.org/case-study/demand-management-for-roads-in-london. This is known are earmarking tax, where a specific portion of taxes or charges is used for specific purposes. This is not practised in Malaysia, as public goods programmes and initiatives are financed from general taxation20Azuddin, A., Razak, Z. and Omar, N. (2021) The Financing Of RapidKL Bus Services Needs A Major Rethink. The Centre. Available at: https://www.centre.my/post/how-transit-bus-services-are-financed-needs-a-major-rethink.

If DBKL does reinvest congestion charges revenue, then it would be prudent to focus on these areas:

- Pedestrian access and infrastructure

- Micro-mobility initiatives and infrastructure

- Development and enforcement of dedicated bus lanes

- Complete pedestrianisation of key urban areas

- Improving feeder bus service and network

DBKL manages its feeder bus service, GoKL which plies several routes throughout the city and its urban edges. However, GoKL does not have the same network reach and expanse as Rapid KL which covers a majority of the Klang Valley region, including Kuala Lumpur21Portal Rasmi Dewan Bandaraya Kuala Lumpur (2021). Bas Elektrik Dan Laluan Baharu Bas GOKL. Available at: https://www.dbkl.gov.my/bas-elektrik-dan-laluan-baharu-bas-gokl. Increased revenue from congestion charging may allow DBKL to expand its bus service network throughout the region, similarly to the Selangor State Government’s Smart Selangor feeder services and cover gaps left behind by Rapid KL’s axed services over the recent year.

Conclusion

As Kuala Lumpur’s traffic is expected to return to pre-pandemic levels are we move into and past the endemic phase, DBKL needs to seriously consider how it wants to deal with the city’s traffic management. Additionally, if the local council is committed to making Kuala Lumpur a livable urban space, it needs to consider carving an environment that is conducive to good well-being for its urban citizens.

Congestion charging is one such policy that can achieve those objectives. While it is politically sensitive and potentially unpopular due to its approach of charging a levy on users, its implementation should happen concurrently with the improvement of public transport services and first-last mile infrastructure. This would make the shift from private vehicle use to public transit much easier, alongside encouraging more sustainable forms of transportation.

Kuala Lumpur has the right tools set in place to implement congestion charging — all it needs now is the political will.

The author would like to thank Danesh Prakash Chako for his valuable comments.