A few months ago, Finance Minister Lim Guan Eng revealed that Kelantan was the largest state debtor, requiring RM388 million in financial assistance from the federal government1. This came at the end of the federal government’s decision to then suspend the East Coast Rail Link (ECRL) project that the government administration claimed was putting financial stress on the nation’s coffers. The ECRL, a legacy project from former premier Najib Razak’s administration was intended to boost the East Coast economy which had typically been in dormancy. In recent developments, however, the federal government has considered reviving the project but by first entering negotiations with the project partner China, to shave off as much cost as possible2.

Currently, to sustain its economy, Kelantan is turning to logging to sustain state coffers. In 2016, logging alone contributed to 29.12% of the state revenue3. This has courted controversy when it comes to environmental sustainability as well as the prevalence of illegal logging that plagues the state. There is a suggestion that the recent increase in logging activities is what contributed to the state’s annual flooding crisis in recent years4. Apart from environmental concerns, it is also rampant logging that is driving out the indigenous Orang Asli from their native territories5.

In light of these criticisms, Kelantan lawmakers have pressed the federal government to give the state their oil royalties, which had long been denied under the former Barisan Nasional administration since the 1990s6. Returning the state’s oil royalties would give Kelantan RM 1.5 billion annually, and help develop the state where investment and external development efforts have failed. While the long-awaited payment of oil royalties may be able to alleviate the state’s economic condition, there are concerns whether the political administration would be able to improve Kelantan as a whole, and whether it would be funnelled into proper development areas7.

To understand this, we would need to delve a little deeper into Kelantan’s economy.

Economic Opportunity and Reality

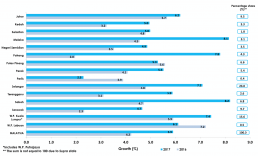

In 2016, Kelatan contributed 1.8% to the nation’s overall GDP, placing it second-lowest next to Perlis. Performance-wise, Kelantan has consistently came out bottom-tier in GDP contribution. While there are many factors surrounding this, we first need to examine the state’s economic stature and the industries it’s active in.

Last year, some months before the 14th General Elections, the Malaysian Investment Development Authority (MIDA) presented a case for investing in Kelantan and laid out the economic and industrial opportunities present in the state8.

It comes to no surprise that agriculture comes second to the state’s GDP output, given its recent rise in logging activities (legal or otherwise). In the MIDA address, the state’s investment arm identified a few areas of economic opportunities, and ones that also partially hinges on the predicted success of the ECRL project.

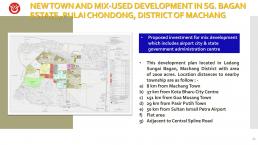

While these investment proposals are proposals at best, there is an eye on harnessing Kelantan’s strategic location by the sea as well as investing in mixed developments to encourage growth and vibrancy – across social and economic fronts. Investment proposals, however, remain only on paper if not reflected against the current socio-economic reality.

With regards to the oil royalties mentioned earlier, under the former Barisan administration, Kelantan had, for decades been denied access to its petroleum resources, with the processing plants and exploration projects located in its neighbouring state (and former Barisan stronghold) Terengganu9. As far local entrepreneurship goes, the recent Kelantan Trade Expo 2019 had vendors presenting natural health products, beauty and cosmetics, fashion, food and beverages and artisanal crafts10. These factors, among others, are indicative of the entrepreneurship and industrial limitations in the state.

This lack of economic activity has driven their citizens to seek opportunities elsewhere, either crossing the border into Thailand or venturing further south-west to developed states such as Selangor11. The latest number of local youths outside Kelantan currently stands around 250,000 out of the state’s 1.8 million population, a figure that indicates a lack of economic opportunities for a labour force that is competing against a national economy that is increasingly competitive but equally stagnant.

Labour market aside, there is also the need to consider Kelantan’s infrastructure, facilities and its policies conducive to outside investment. Last year, the former Minister of International Trade and Industry Datuk Seri Mustapa Mohamed indicated that despite foreign companies being interested in setting up cement manufacturing projects in the state, the lack of proper infrastructure proved a challenging roadblock to these potential investments12. There is also a need to consider the state’s annual flash floods – likely preventing the stability for businesses to set themselves up in Kelantan; the lack of adequate preventive measures not inspiring confidence in those wanting to invest in the state.

It should be said, however, that the Kelantan government recently introduced several incentives to draw investors into the state. Among them, an assessment tax exemption to reduce operation costs, as well as an expedition process for land grants13. While these incentives are in the right direction, it is important to examine the state’s political economy, and why the context in which it landed itself in this decades-old economic deadlock. It is not enough to introduce economic policies if the administrative and communal ideology does not integrate well.

The PAS appeal

Critics have pointed out that the Kelantan government’s zeal to implement religion across the board may be one of the factors keeping investors away, as well as diverging its focus from improving the state’s livelihood and economy14. A major example of this is the persistence of PAS President Hadi Awang in tabling a private member’s bill intended to empower the Sharia courts to carry out a stricter form of punishment under hudud15. Just months after GE14, in the name of upholding Sharia law, Kelantan caned a lesbian couple and imprisoned and caned a sex worker (a widow working out of desperation to support her children)16.This is the mission PAS, as a state government operates on – their singular goal being the implementation of Sharia law throughout the state and emulating an Islamic way of life and administration.

But why would the Kelantanese continue to vote in PAS for decades, despite the political party’s apparent lack of economic acumen? And the disadvantaged position PAS, as an opposition state government puts them against the federal government. Prominent academics have traced the strong relationship Kelantanese have with PAS as a spiritual resistance against the overwhelming power of Barisan Nasional17. In fact, the interpretation of religious struggle understood by the Kelantanese is how Islam democratises power relations between the common public and those in power18. PAS, in its decades under the stead of the late Nik Aziz, interweaved religious struggle with the political; Islam became a tool to resist against the then-oppressive powers of the Barisan Nasional federal government.

This, when coupled with the historical influence of the Iranian Revolution in establishing a theocratic state, and the spread of Saudi-sponsored Wahhabism throughout Muslim world, illustrates a revival of a romanticised “Golden Age of Islam” where religious doctrine and its practice equalises social justice for all19. Even Malaysia, under the first premiership of Mahathir Mohamad, spared no expense at strengthening and establishing Islamic institutions such as the International Islamic University (IIUM) and Department of Islamic Development Malaysia (JAKIM) to prove Barisan Nasional’s commitment to Islam, and as a political pushback against PAS20. The “Islamic state”, as one can infer, promises religious governance, and social and economic justice guided by Islamic principles.

However, that Kelantan has consistently voted in PAS as its state government for decades would speak to the public awareness of the Barisan administration’s agenda, while still reaping the rewards dealt by the then federal government’s attempt to one-up and compete against PAS’s influence.

Another perspective to consider is tactical voting by the Kelantanese to ensure Barisan Nasional would never gain a foothold over the state. In an interview last year, PKR Vice President Rafizi Ramli, analysing the results from his research firm INVOKE’s GE14 electoral study, described how the Kelantanese voted for PAS because they saw the religious-party as a stronger political opposition21. To beat Barisan, they voted for a more experienced and proven PAS, than an opposition coalition hastily cobbled a year before the elections. This course of thinking led in the fall of Barisan in Terengganu and PAS’ claim over the two East Coast states. Despite Pakatan Harapan having taken over the reins of Putrajaya, the new federal government’s inexperience in governing could speak as a confirmation to the Kelantanese voters of why PAS may have been the better option.

Kelantan is seemingly caught in a cycle. They vote PAS to resist against federal powers. PAS, being more religiously-focused than economic, fails to develop the state or attract investment. Coupled with the fact that during the years of Barisan as the federal government, Kelantan was discriminated against when it came to annual budgets and development.

In light of recent negotiations between Kelantan and the Pakatan Harapan government, as well as the possibility of resuming the construction of the ECLR – it is worth exploring how the PAS government’s commitment to religious administration would affect economic growth in the state.

Kelantan’s opportunities and challenges

Halal Hub

Kelantan has been definitively recognised as a state aspiring to implement the Islamic way of life in its sociocultural and administrative landscape. While its culturally-conservative approach to governing often makes it a target of criticism, PAS’ dedication to religion is also what makes it a strength to its constituencies who have consistently voted them for decades22. This despite the state’s lack of economic development, cultural restrictions, social ills, and increasingly harsher punishments meted out through the Sharia courts.

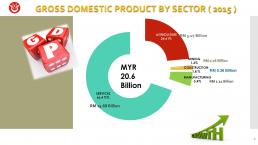

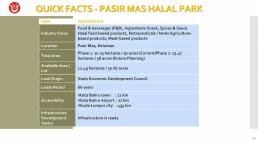

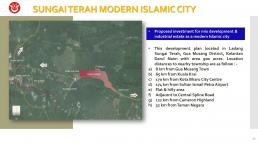

This religious “strength” was recognised by the then-Barisan government when they proposed a Halal Hub in Pasir Mas, and an Islamic city development in Sungai Terah (see images slides above). Both these developments capitalise on the PAS state government’s strict observance of religious principles and entrust them to integrate it through with economic developments. The Halal industry is an economic opportunity ripe for the picking, with a growing global Muslim population looking for Sharia-compliant products and services. In 2017, Malaysia ranked in investments worth 13.3 billion, and reached an export value of RM43 billion, proving the nation’s as a leader in the global Halal market. The country’s Halal industry alone contributed to 7.5% of the national GDP23.

While Kelantan may lack the economic experience to manage large-scale business and investment, there is an opportunity with the state to work together with federal institutions, notably JAKIM to develop the state into a Halal hub. The Pasir Mas Halal bub’s focus is already placed on domestic products such as food and beverage, nutraceuticals and halal meat production. The completion of the ECRL would connect the state’s industry to major ports on the peninsula coast, notably Kemaman and Klang. This would allow a streamlined export of domestic goods, allowing Kelantan produce to be made more accessible throughout the country and global points of access.

There is a widespread cultural and historical acknowledgement that entrepreneurship is part of Kelantanese culture. 2013 records from the Kelantan Malay Chamber of Commerce (DPMK) indicate that commerce, at 41% is the largest sector the Kelantanese have involved in24. In fact, the state capital’s market, Pasar Siti Khadijah is an exemplary microcosm of Kelantan’s entrepreneurial spirit, dominated largely by women and the beating heart of Kota Bharu. What these local businesses lack is a link to the global market, and the Halal hub combined with the ECRL may prove an opportunity to connect the local to the global – capitalising on the Kelantanese entrepreneurial spirit.

Culture and Tourism

Kelantan is rich with culture, being distinct from other states in the Peninsular due to its historical and cultural ties to its neighbour, Thailand. The state government’s tourism website lists a variety of cultural and historical attractions, natural outdoors, local cuisine and crafts25. The state has tourism potential and an opportunity to generate an income from this revenue. In fact, a research paper on the Kelantan tourism experience indicated that international tourists often came for the state’s natural resources such as beaches, caves, rapids, and highlands26. The study also showed that Kelantan functioned as a transit state between Thailand or Pulau Perhentian, Terengganu, with tourists often staying up to a week. European tourists formed the largest segment of tourists who visited the state.

However, Kelantan sits at a conflicting position on its stance towards its cultural heritage. Over the decades, the state administration, in their pursuit to incorporate Islam into the Kelantanese landscape, had banned its traditional performances, the Mak Yong dance and the shadow play, Wayang Kulit among many others. Despite calls from civil society, heritage institutions and even the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (Unesco) to revive and save the arts – the state has been steadfast in removing it from its cultural canon27. The Kelantan administration had also restricted entertainment outlets, stating that the state does not require a cinema outlet and resisting calls to develop any form of entertainment centre 28. The cinema debate has been a long-standing issue for the past three decades, with the state giving reasons such as prevention of khalwat, free and unregulated mingling among sexes and more recently, the availability of social media as a reason to not build cinemas.

The administration’s sober approach to its cultural and social landscape, however, does not diminish the locals from participating in a lively nightlife. The state’s capital city, Kota Bharu is alive at night with cafes, restaurants and pop-up funfairs becoming social spaces for the community29. Additionally, areas surrounding the capital such as Wakaf Che Yeh are host to sprawling street markets that only open in the evenings until late morning, offering a variety of goods and food stalls30.

The Sufahani et al. (2016) study on the Kelantan tourism experience outlined three tourism areas of focus for the state to develop, (i) natural outdoors, (ii) culture, craft and heritage and (iii) shopping. When synthesised with the Kelantan state government’s vision for an Islamic economy through its halal hub, there is an opportunity for Halal tourism. According to the 2014 Crescentrating’s Halal Friendly Travel (CRaHFT) Ranking, Malaysia ranked highest in the Halal-friendly Muslim destination among The Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) member countries31. In recent decades, Malaysia has actively targetted the Middle-East and established tourism initiatives such as Islamic Tourism Centre (ITC), the 2008 OIC Global Islamic Tourism Conference and Exhibition and World Islamic Conference and a “Feel At Home” campaign among many others.

Kelantan, despite its lack of economic development and infrastructure, as well as its conservative attitude towards entertainment and culture, may be best positioned to work with the federal government to develop the state as a Halal destination. The state adminstration’s Islamist approach may not suit the broader Malaysian cultural context, but may draw interest from international Muslim tourists who are concerned with the Shariah-compliant Halal approach.

Conclusion

Over the decades, Kelantan has been one of the country’s worst-performing states in terms of GDP output and economic development. There are many factors contributing to this, ranging from the state government’s lack of economic acumen to the withholding of oil royalties since the 90s, and the PAS-led government’s agenda on implementing holistic Sharia law. Despite these limitations, Kelantan has the potential for economic development. This is clear in its religious stance providing it with a workable basis for a halal hub, to the development of the ECRL that will link its economy to the rest out the country and potentially, global network. This, as well as areas of tourism opportunities in capitalising its heritage, arts, shopping and natural assets.

The state of Kelantan’s economy is usually misunderstood, and often not paid attention to due to a closer focus on its political development in the area of Islamic administration, both on a local and national level. Given the right guidance from federal institutions, combined with investments and collaborations with foreign companies – Kelantan, one of Malaysia’s worst-performing states has a potential to harness the “strength” of its Islamic agenda and channel it into its economic development.